A Tale of Two States

On November 2nd, 1889, Benjamin Harrison, ranked #30 in C-SPAN’s ranking of US Presidents, probably sneered as he drove a knife into the heart of Dakota Territory, dividing it forever along an East-West meridian. When he signed the documents formally creating two new states, the President famously (and cutely) shuffled them, preventing onlookers from knowing which of the two acts was signed first, and prohibiting either side of a budding rivalry from having an early upper hand. While political decisions over the divvying up of land in the United States almost never, ever, ever go wrong, the division of the Dakotas is the one rare mistake in an otherwise pristine history.

The Dakota Territory wasn’t an enormously large territory. At 147,877 square miles, North and South Dakota combined would still be smaller than Alaska, Texas, and California, and only barely larger than Montana (147,039). Today, with a combined population of 1,642,312, a united Dakota would have fewer people than 39 other states, sitting between Idaho and Hawaii in population ranking.

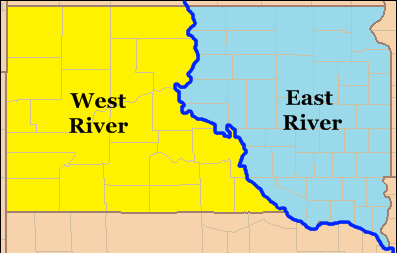

Dakota didn’t have to be broken up. It was big, but so was Montana. So were Texas and California. Some large territories were based on cultural or population differences, but the Dakotas weren’t. Instead, a team of politicians drew a line down the middle of the state. But while North and South Dakota aren’t particularly distinct halves of a larger Dakota, the more naturally-crafted Eastern and Western halves of the states are. If you grew up in South Dakota, you knew this conflict as East River vs. West River. If you lived in North Dakota, I don’t know what you called it. Like most people in South Dakota, I don’t know anyone from North Dakota.

Most South Dakotans will tell you the East vs. West rivalry is tongue-in-cheek, at least most of the time. Still, the differences cleaving the two halves of the state apart are real, and deeper than the Missouri River.

The Differences

Geology & Climate — The distinction between the two states goes back over ten thousand years, when the entirety of Eastern Dakota was covered by a glacier, and most of Western Dakota was not. Millions of years of glaciation led to drastically different soil compositions, making the Eastern half of the region more available for agriculture. Land on the Western half of the Missouri River is, on average, elevated higher than land in the East, which receives significantly more rainfall.

Agriculture — Blessed by the mighty glaciers, Eastern Dakota is harbors a flatter, more nutrient-enriched soil than its Western counterpart, making farming the dominant agricultural practice East of the Missouri. On the other side, cattle ranching is more viable a practice.

Economy — Agriculture was the dominant industry on both sides of the Missouri river for most of the region’s post-colonial history, though starkly differentiated by the crop farming-cattle ranching gap. Moving beyond one of the biggest money makers for Dakotans united, the two sides of the state are still very different. The western region of the state is more rich in oil and mineral deposits, with mining operations mostly limited to the black hills region and entirely limited to the western side of the river, and the Bakken oil formation contributing significantly to the economy of western North Dakota. Meanwhile, east of the Missouri, urban-centered service work is at the core of the more modern East Dakotan economy. The Black Hills and Mount Rushmore serve to stimulate a more tourist-oriented economy in the West, while flat cornfields and the city of Sioux Falls do not.

Population & Population Density — In the grand scheme of it all, both sides of the Missouri are pretty sparsely populated, but the Eastern half of each state is significantly less sparsely populated. The most populous city in each state (Sioux Falls in South Dakota, Fargo in North) either straddles or comes close to straddling the state’s Eastern border, and most of the urban areas in both states exist on or near a straight line connecting the two urban areas. Of the ten most populous cities in South Dakota, eight of them are East River. In North Dakota, six of the top ten are located in the state’s eastern half, with eight east of the Missouri river. The metro areas of Sioux Falls and Fargo are, together, responsible for over 30% of the population of greater Dakota.

Politics — West Dakota would be a solid red state, and would have voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election, whereas East Dakota would be more of a purple state and would have voted for Donald Trump. It’s the little things.

Geography — Population centers in both states are heavily polarized, with Sioux Falls, Fargo, and Grand Forks hugging their states’ eastern borders, and Rapid City closer to Wyoming than Pierre. When people in Western Dakota travel to “the city”, there’s a pretty good chance it’s Denver, while Eastern Dakotans prefer a pluralized travel to “the cities” of Minneapolis and St. Paul. The people of Eastern Dakota set their clocks to Central Time, those of Western Dakota to Mountain.

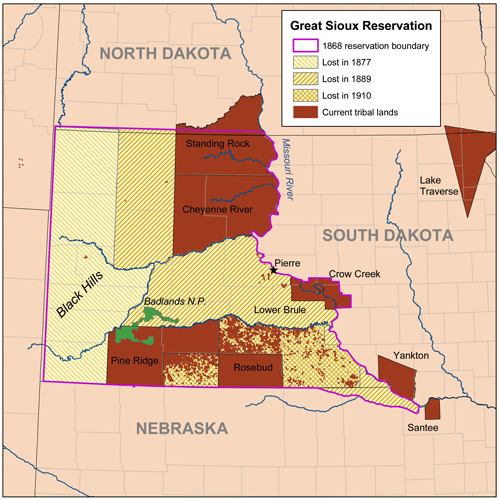

Native Americans — The original draft of this post included space for the long history of conflict between white settlers and the Native Americans, a history that saw the drastic shrinking of their territory from all, to half, to less than a quarter of the states’ lands. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 established the Western half of South Dakota as the Great Sioux Reservation. In the years that followed, lands reserved to Native Americans were steadily doled out to primarily white settlers until the limited number that still exist today were left. Reservations exist on both sides of the Missouri, but most are on the Western half. Western South Dakota also has a heavier concentration of Native Americans than Eastern South Dakota. The existence of indigenous people on either side of the river doesn’t really play into this argument at all, but leaving them out completely felt worse.

Conclusion

So what’s my point? The damage is done. North and South Dakota have existed as separate entities for 130 years. To fundamentally reorganize two states would take years of effort, all to placate one person who left South Dakota five years ago. If North and South Dakota never reorganize and decide to stay in their current unhappy marriages for the rest of their lives, will they be doomed? Maybe not. Probably, but maybe not. The real question is: can I ever forgive them? Realistically? Yeah. I don’t think about it that much.

What about you? Tweet at me, scoundrels.